I keep telling everyone “it’s been like a death in the family.” But my take is that it was a preventable death.

I liken it to a diabetic who dies for lack of insulin. Not because insulin hasn’t been invented. Not because no one knows that’s the right treatment. But because there’s no money to buy it,

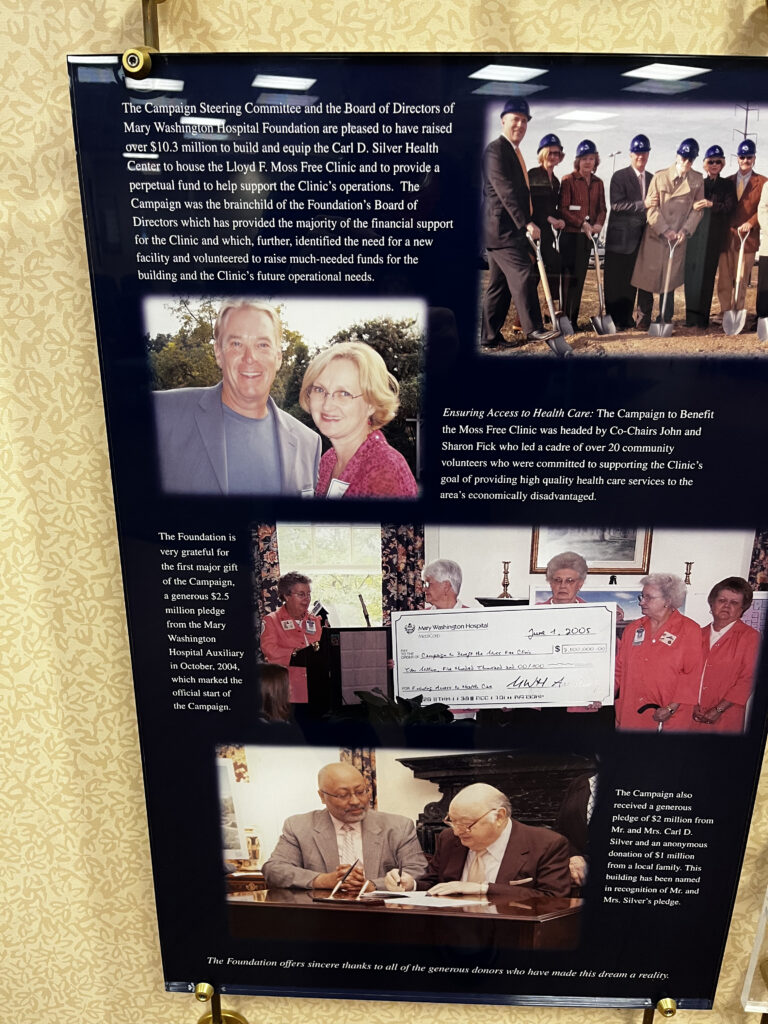

The display in the Moss waiting room with Mary Washington Hospital Corporation's generous, but unfullfilled promise to "provide a perpetual fund to help support the clinic operations"

I use this somewhat tortured analogy to explain what happened to the Moss Clinic, where I was medical director for the last 15 years, and as you likely have heard, closed abruptly in the middle of the month.

It didn’t close because of lack of expertise to run the place. It didn’t close because of a shortage willing staff (the staff at the clinic, who could have been earning more elsewhere, were there because they believed in the mission of the clinic as expressed in its founding document “to assure each person in the region access to prompt and exemplary medical attention,” and pulling the plug on such a devoted staff was especially terrible.)

The clinic closed because we ran out of money – to the point of not even having enough to cover the next pay period.

The Need

In 1991 the Virginia legislature passed a Joint Resolution expressing concern about the underserved, medically indigent in the Fredericksburg area.

This prompted the formation of the Fredericksburg Area Regional Health Council (FARHC). This committee, spearheaded by Lloyd (Jeppe) Moss senior, created the Lloyd F. Moss Free Clinic - one of a nationwide network of 1200 much needed “safety net” clinics. A “patchwork of providers, funding, and programs tenuously held together by the power of demonstrated need” to quote the Institute of Medicine.

Starting in the Amy Guest Ward of old Mary Washington Hospital, then moving to the old Health Department building on Hunter Street - two bare-bones locations with minimal overhead – the clinic grew steadily, expanding services adding dental, behavioral health, psychological counselling, a social worker, a health insurance navigator, and a busy pharmacy acting as a “central fill,” meaning they provided prescriptions for 14 other free clinics.

The success of the clinic was acknowledged by numerous awards from churches, charities, J C Penny, the Chamber of Commerce, Wachovia, The Virginia Healthcare Foundation and other community organizations for “Merit in Exemplary Effort in Improving Healthcare for the Medically Underserved” as one award put it.

In 2004 the clinic and Mary Washington Hospital Foundation cohosted a fund raising effort - “Ensuring Access: A Campaign for the Moss Free Clinic.” This raised an impressive $10.3 million.

Some $4 million and change of this was spent on a building - a grand, affair with multiple exam rooms, a large nurse’s station, multiple offices on two levels, storage rooms, a conference rooms, and most of the upper floor taken up by the John F. Fick Conference Center. This building that has housed the clinic was opened with great fanfare by Sen Tim Kaine in 2007.

Of note was that MWHC retained ownership.

The rest of the money was put in an account managed by Mary Washington Hospital Foundation, with the foundations president Xavier Richardson being appointed to the FARHC.

Wrangling for Dollars

We gradually consumed the banked portion of the money collected – though tracking the progress of those diminishing funds always seemed challenging.

Foreseeing that we would spend all the money, MWHC offered to take over operations. But the FARHC board was concerned the essential mission of the clinic would be lost and that the takeover would not keep the dental side going, nor support the pharmacy in providing for so many other needy clinics,.

After consulting with an outside company that calculated we could “go it alone” the MWHC offer was rejected.

We redoubled our efforts in grant writing and fund raising to meet the clinics annual running expenses of $2.2 million – but found our skills lay in the field of healthcare rather than wrangling for dollars. Our fund-raising skills were not commensurate with our caring for the medically indigent.

Things were made worse by MWHC withdrawing support it had been providing for IT, citing concerns about security of their system. They also withdrew payroll management, maintenance and other services making it harder still to meet the clinic’s annual budget.

This seemed to be a bit of a reflection of some disenchantment.

Back in 2004, it was all coziness and cooperating. There is a picture in the clinic waiting room of the Campaign Steering committee and the MWHC Board of Directors looking pally and chuffed in hard hats with shovels, breaking ground on the site for the new clinic building, with a legend grandly promising to “provide perpetual funds to support the clinics operations.”

But, apart from a general obligation to provide charitable services equivalent to what they don’t have to pay in taxes – because MWHC is a non-profit, meaning they don’t pay federal or state sales, income or property taxes (all those taxes we gripe about having to pay but which provide an endless list of necessities like schools, roads, defense, law enforcement). Apart from this, they are under no particular obligation to support the Moss clinic.

Similarly, Spotsylvania Regional Medical Center, a for-profit establishment owned by Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) that has some 180 other hospitals nationwide, and an annual income around $5 billion, have had representation on the FARHC, but have not provided financial support.

The Devil Take the Hindmost

In a country where healthcare is not seen as a right. Not seen as something that should be universal and provided out of taxes – as it is in every other equivalent industrialized country in the world.

Where healthcare cost nearly twice as much as any other country ($12,197 per-head for 2021 compared with $6,514 for the average of other comparable countries) means there are millions of un-insured and under-insured. And people going broke from medical bills – while hospitals, doctor's, pharmacies, medical device manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies are wildly profitable (to the point they are being snapped up by investment companies and hedge funds), all enabled because the wealth of the industry provides massive lobbying clout to maintain the status quo.

This is what creates the medically indigent – that the legislature was so worried about back in 1991. A problem that has only got worse with the region’s massive growth. Those people the Moss clinic staff and I worry about. A population that are reliant on the largess of the community.

The claim is there is capacity to provide care for all the Moss Clinic patients. Eric Fletcher, senior vice president and chief strategy officer at MWHC seems confident, writing “our community safety net does have the capacity to care for former Moss clinic patients.”

My concern is how well served these patients will be – many of whom have transport problems and rely on the Fred bus coming to the current location. And patients who need the variety of services the clinic provided as a “one-stop-shop” capability.

I fear it’s going to be like the Joni Mitchells song, Big Yellow Taxi.

“You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.”

1 Response