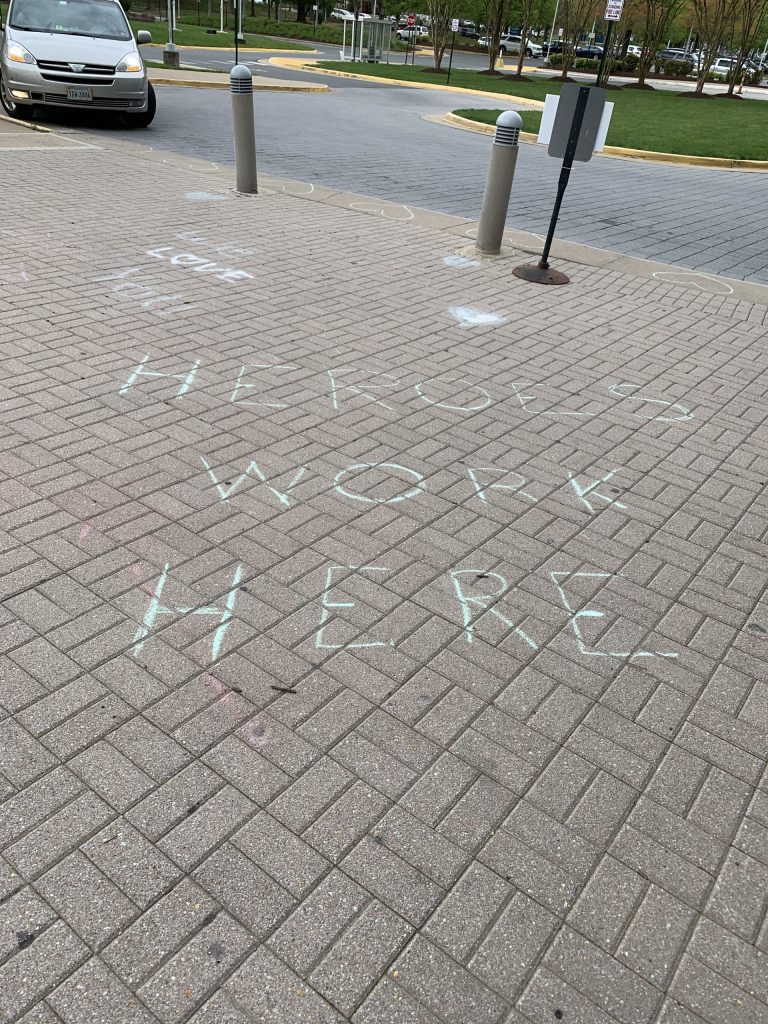

I took my life in my hands the other day - wanting to see how things are on the front lines of the COVID-19 epidemic.

To do this, I went and shadowed Grace Frye one of the nursing team on 2 South - the unit that has been repurposed from surgical recovery to managing COVID-19 patients.

Having to be there at 7 am for change of shift I joined these gladiators in their masks, gloves, hats, eye protectors and gowns – and after wearing an N-95 mask, for just a couple of hours, I understand those pictures of nurses coming off 8 or 12 hour shifts looking exhausted, with creased and battered faces.

We rounded, with Grace rolling her high-tech computer cart from room to room. Not only were we dealing with people sickened by a lethal virus I saw, but she was managing patients on anticoagulants in danger of bleeding or clotting. Patients on experimental drugs like remdesivir and hydroxychloroquine. A woman 15 weeks pregnant, with a history of diabetes, who was having abdominal pain and an ultrasound suggesting cholecystitis (infected gall bladder).

An asthmatic with COVID-19 pneumonia but also with unexplained elevation of his liver function tests – and who didn’t speak English so communication is through an i-pad and a remote translator.

To minimize the number of people that have go in the patient’s room, she does not have the usual support of a nursing assistant. And is acting as go-between for doctors, also talking to patients by video link. But in the middle of it all there’s still the touchy-feely stuff, like ordering a banana and milk for one patient who hadn’t got to put in his breakfast order – though not without having to clarify with dietary he was on “contact isolation”, and not “protective isolation” when fresh fruit would be an infection risk.

Then there’s the emotional stuff. One of the other nurses told about holding an i-pad so an isolated, dying patient could say their goodbyes to the family. “She was crying in the break room when she told me” Grace noted.

A Realistic Fear

Despite the personal protective equipment, - which has just kept pace with need, partly by enterprising nurses replacing perished elastic on N-95 masks that had been in storage – some of the nursing staff have got sick.

At the change of shift huddle, the team leader not only tried to boost morale, but asked for “thoughts for Billy” a nurse who had been working on 2 South, “who is on a vent’ at VCU and not doing well” (though at a second visit I made I was told he had improved and was off the ventilator after receiving convalescent serum).

Fellow team member Cassie Huot exemplifies why everyone worries about working in this place. “I was tired, ran a fever, with cough, chills,” and had that peculiar tell-tale symptom of loss of sense of smell she told me. A nasal swab test confirmed that she had COVID-19. She had just returned after 3 weeks sick leave – and in that way that nurses just can’t help enough, she is now bound and determined to donate convalescent plasma to treat others.

Like so many people she doesn’t know where it came from. No patient that she knows of – “possibly from co-workers. Possibly when shopping” she told me. But then her husband and 4 year old daughter got sick. But they couldn’t get tested, making the point that, although things are improving, availability – as well as accuracy – of testing are still a concern.

“Somehow you adapt to the stress” Grace told me, and she’d rather be working than like her husband who was not able to work and “is fretting at home going stir crazy looking after the kids and watching the news on TV.”

Dealing With It

A report in JAMA about the adverse effects on nurses in China showed 50.4 percent got depressed. 44.6 had anxiety and 34 percent suffered from insomnia, so it would appear that this pandemic is beating on the nurses pretty badly – and presumably on other healthcare workers as well.

A quick search of the internet showed zillions of sites talking about coping strategies. A lot of it the basic stuff (we should all do) – exercise, healthy diet (primarily plant based); get enough sleep. Even seek counselling.

But also some specifics like take a break from the news – which I would whole heartedly embrace as it all seems to be gloom and doom. Keep up your social connections as well – discover the wonderful new world of Zoom.

The support from Mary Washington administration has been wonderful Grace told me, allowing a lot of autonomy in workflow and what personal protection to wear. Plus paying for all shifts that would have been worked, even when people are out sick. And keeping people on the payroll – “in contrasts to other hospitals”, Grace told - saying she’s heard about nurses being let go – and not even in person, but “by text.”

They’ve received a lot of support from the community– “gift baskets, freebee services for our cars from local service stations. And more pizza and tacos than we know what to do with.”

The job is heartbreaking and scary at the same time Grace told me, but she also sees the effect of what I call “helpfulness therapy.” When you do something to help someone else, it’s a moral boost for you. This crisis has brought the team together. They have bonded she says. And she feels empowered.

Confronted with the danger every day, “doesn’t this outweigh the benefits?” I asked her. This sparked the commitment, compassion and dogged determination to help others – that so many of these angels in scrubs seem to have.

“I’m not quitting” she told me simply.

1 Response